”"The tattoo has an attraction comparable to that of opium: once under its control, all resistance becomes futile. For those who fall prey to it, nothing else matters."

Akimitsu TakagiExtract from his first book 'Shisei Satsujin Jiken' (1948)

Akimitsu Takagi (1920-1995) is one of the greatest Japanese crime writers of the 20th century.

Born in Aomori in northern Japan, Akimitsu Takagi became one of Japan’s most popular authors in the period following the end of the Second World War. Born into a family of doctors, a scientist trained at Kyoto University with the country’s elite, Takagi left the aeronautical sector after the defeat and invested himself in writing in an unusual way, on the advice of a fortune-teller. His interest in tattooing was a determining factor in the plot of his first novel: Shisei Satsujin Jiken. Published in 1948, this investigation into the murders of tattooed people in devastated post-war Tokyo was an immediate success. It launched his career. When he died in 1995, he left behind more than 250 stories. In Japan, his books sold several million copies.

Repères

Release of the first book by Akimitsu Takagi: 'Shisei Satsujin Jiken'.

Film adaptation of 'Shisei Satsujin Jiken' by director Mori Kazuo.

First translation into English of 'Shisei Satsujin Jiken' by Soho Press (USA) under the name 'The Tattoo Murder Case".

First French translation of 'Shisei Satsujin Jiken' under the name: 'Irezumi', published by Denoël.

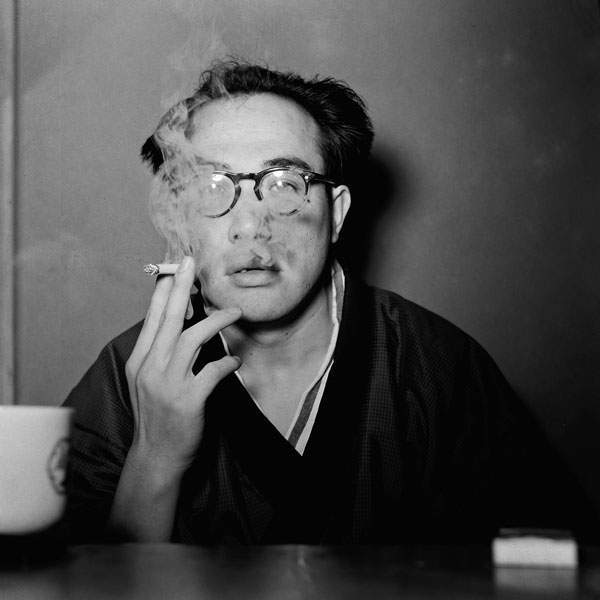

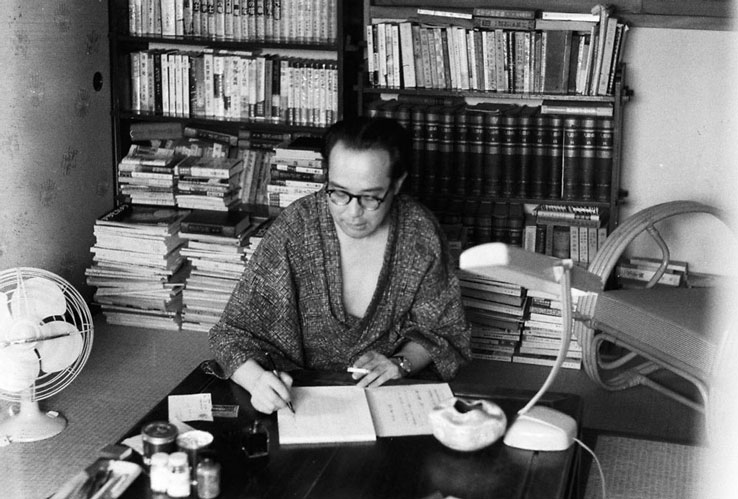

(Akimitsu Takagi at home, c. 1955 - © Takagi A. coll./DR)

Takagi comes into contact with the tattoo scene in Tokyo after 1945, while researching for his first novel, Shisei Satsujin Jiken (Irezumi, in French, The Tattoo Murder [1] in English). The tattoo is indeed at the heart of the book’s plot. It features the murders of tattooed people, victims of cursed motifs in a ruined Tokyo where snake-skinned femme fatales, tattooed skin collectors and tattoo enthusiasts’ clubs attached to the spirit of ancient Tokyo meet

Now a successful young author, Takagi expands his connections in the amateur scene where he deepens his passion for tattooing. He became familiar with the tattoo artists and the tattooed people he met in the masters’ studios. A privileged observer of this shadowy world, unknown to Japanese society because of the long prohibition that forbade tattooing for almost 80 years (from 1872 to 1948), Takagi became a leading witness when he began to document it.

He thus photographed the greatest tattoo artists of the time. Their names are: Horiuno II, Horiuno III, Horigorō II and Horigorō III or Horiyoshi II, the famous tattooist of the Azabu district. Takagi also photographs the tattooed works he observes on the bodies of their clients. Singular works of undeniable beauty, as they have been done in the Japanese capital since the Edo period (1603-1868), when the culture of figurative tattooing spread among the working classes, in the wake of the success of polychrome prints.

And then there are the tattooed women. Their repeated presence in Takagi’s images is unexpected. The writer-photographer thus lifts the veil on a little-known part of the tattoo artists’ clientele. Women who go against the prejudices that would suggest – as the observation of the prints would suggest – that tattooing is reserved for men. They also echo the origin of Takagi’s passion for tattooing, a passion that goes back to his childhood in a public bath.

If photography allows Takagi to satisfy his obsession for tattooing, thanks to it he also carries out a capital work of memory. Photography furthermore provides a pertinent solution to the real threat to this shadow art: oblivion. After all, how can one keep track of an art that is essentially ephemeral? Besides, without memory, what history of art? And without history, what recognition for the master tattoo artists whose works testify to an excellence comparable to that of any Japanese craftsman raised to the rank of “living national treasure”?

[1] The Tattoo Murder, Pushkin Press, 2022.