”"The tattoo has an attraction comparable to that of opium: once under its control, all resistance becomes futile. For those who fall prey to it, nothing else matters."

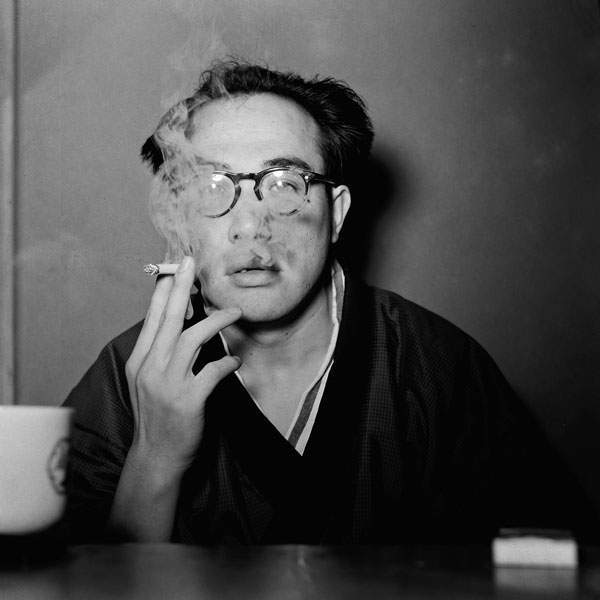

Akimitsu TakagiExtract from his first book Shisei Satsujin Jiken (1948)

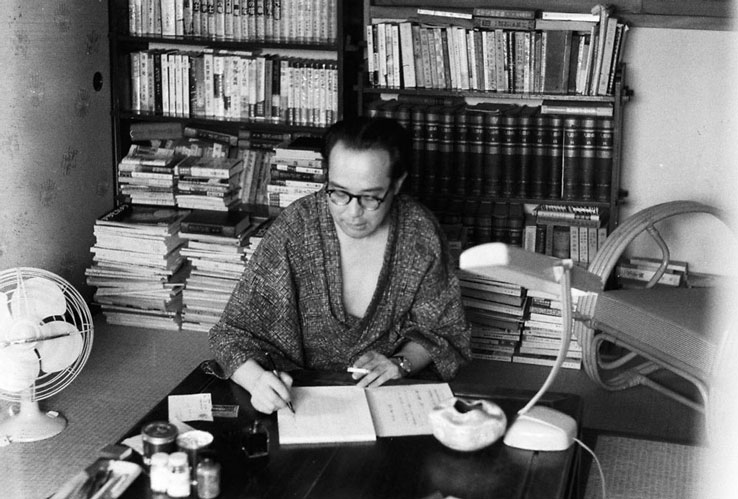

(Akimitsu Takagi at home, c. 1955 – © Takagi A. coll./DR)

INTRODUCTION TO THE ENVIRONMENT

Takagi came into contact with the Japanese tattoo milieu in Tokyo after 1945, while researching for his first novel, Shisei Satsujin Jiken (Irezumi in French, The Tattoo Murder [1] in English). Tattooing is at the heart of the book’s plot, which features the murders of tattooed people, victims of cursed motifs, in a Tokyo in ruins where a snakeskinned femme fatale, a collector of tattooed skins and a club of tattoo enthusiasts attached to the spirit of the old capital meet.

A PRIVILEGED WITNESS

Thanks to the success of his first novel, which focused on traditional Japanese tattooing (irezumi), Takagi broadened his contacts in the closed world of tattoo enthusiasts and artists. He deepened his passion by visiting the workshops of master tattoo artists, discovering a clandestine world rich in tradition. This milieu remains largely unknown to the Japanese general public, due to the ban on tattooing in Japan, in force from 1872 to 1948, a period of almost 80 years.

As a privileged observer, Takagi quickly became a key witness to this marginal culture. His work documenting the art of tattooing in Tokyo makes him an essential figure in understanding the evolution of tattooing in twentieth-century Japan.

TATTOOERS, TATTOED AND TRADITIONAL PATTERNS

Takagi photographs the greatest masters of traditional Japanese tattooing of his time. Among them: Horiuno II, Horiuno III, Horigorō II, Horigorō III, and Horiyoshi II, the famous tattooist from the Azabu district of Tokyo. These emblematic figures of irezumi perpetuate an ancient, virtuoso and deeply codified art.

During his visits to the workshops, Takagi also documents the tattooed works visible on the bodies of his customers. He immortalises tattoos with spectacular traditional motifs, renowned for their aesthetic richness and symbolic significance. These unique creations are a continuation of an ancient artistic heritage specific to the Japanese capital.

During the Edo era (1603-1868), figurative tattoos became widespread among the working classes. This period saw the rise of Japanese tattooing inspired by ukiyo-e prints, with themes drawn from mythology, folklore and war stories. The success of polychrome prints contributed directly to the emergence of these iconic motifs, which have become inseparable from horimono / irezumi.